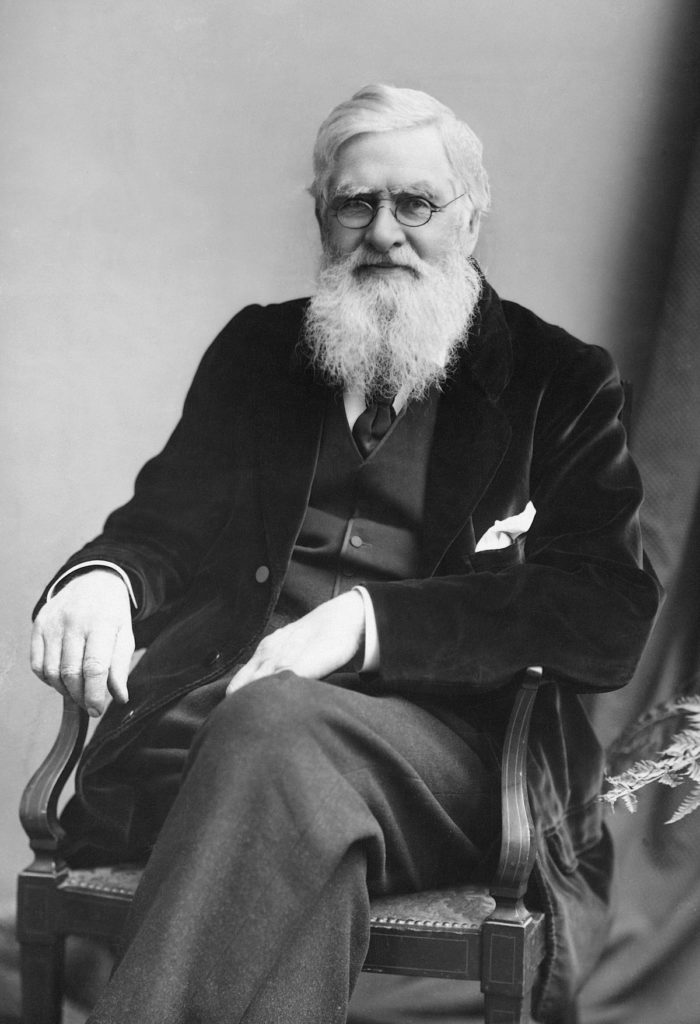

#ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE FULL#

Singapore enthused and amused Wallace, and he made full use of the island’s Goldilocks qualities-remote enough that specimens and information were in demand, but connected enough to England to ensure timely conveyance of letters and specimens and with forests pristine enough that the richness of beetles still surprised Wallace (an expert of the group), but sufficiently disturbed to facilitate his collecting 11, 14. His close study of the Insect and Bird Departments of the British Museum led him to decide that Singapore should be a new starting point for his natural history collections 13. Resolve faded less than eighteen months later, and Wallace was Asia-bound-specifically to the island of Singapore at the heart of Southeast Asia. The day after the meeting he wrote an associate saying that “fifty times since I left Pará have I vowed, if I once reached England, never to trust myself more on the ocean. Three days later, Wallace was present at an Entomological Society meeting 12. It is thus not surprising that Wallace exclaimed, “Oh, glorious day!” on the first day of October 1852 upon reaching England from South America 11. He and his shipmates were rescued after bobbing about for ten days 11. All souls were safely transferred into small boats, but Wallace lost everything except for some papers. On August 6, Wallace was informed by the captain that the ship was on fire.

Wallace and his collections went aboard the ship Helen on Jfor the voyage home. Like Humboldt 6 and Darwin 7, Wallace also made detailed observations of bird plumage variations at the individual level that sustained his ideas about ecological adaptation, sexual selection, and biogeographical trends 8 and which are currently reinvigorated by current macroecology and macroevolution 9, 10. These include the first biogeographic regionalization ever proposed, based on the hypothesis that major rivers acted as barriers, and whose borders still hold up in modern analyses of many taxa 3, but not necessarily for others 4 and his classification of rivers according to the content of their waters, which determine the distribution and diversity of fish 5. The observations he made during these years are beautifully narrated in Wallace’s Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro 2 and established the bases of some of his most important scientific contributions to (bio)geography, ecology and evolution. He was mainly based at Pará, making frequent expeditions to other regions of the Amazon, including a 6-month solo expedition to the Río Negro after splitting with Bates. Wallace spent four years (1848–1852) traveling throughout the Amazon basin (Bates remained eleven), collecting specimens and making numerous observations of the biodiversity, the geography, and its peoples. Edwards’s A Voyage up the Amazon, the volume that ultimately inspired him and Bates to organize a collecting expedition to the luxuriant forests of tropical South America.

Darwin’s The Voyage of the Beagle and W.H.

Chambers’s Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, C. Among other books, he was particularly inspired by C. Wallace was a self-taught naturalist with no formal education, coming from a family of limited resources but with a keen interest in the natural sciences grown during his walks around the British Midlands and nurtured with his readings of the most relevant scientific literature of the time. In April 1848, a 25-year-old Alfred Russel Wallace embarked to the Amazonian Pará with Henry Walter Bates, another enthusiastic naturalist and entomologist, with the idea of earning their living by collecting as many specimens of animals and plants as possible for the growing collections of British museums and private collectors that, at the time, were enthusiastic for the natural history of the tropical regions.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)